For a long time after the discovery of vitamin K, we thought that deficiencies were rare and obvious. We were only partly right.

Now armed with a better understanding of the differences between K1 and K2, there is growing concern that a K2 deficiency is widespread and that the symptoms of this deficiency are not obvious and pass unnoticed.

Chronic deficiencies are a little like a lack of roadwork on a highway. Imagine commuting on a busy highway. To keep it in good shape, the highway needs to be regularly maintained, graded and perhaps paved with fresh asphalt after a hard winter. Without this roadwork, your drive to work may not feel different for a few months, or even a few years. Then one day you’ll drive through a really big pothole. Bam!

Where did that pothole come from? Not doing enough roadwork was partly responsible, but it’s pretty hard to pinpoint the precise cause.

Unlike K1’s direct impact on blood clotting, a K2 deficiency may not have any acute signs. Instead, K2’s role in our biology is long-term and systemic. A chronic deficiency of K2 may take years to manifest – years before we see decay to our cardiovascular or skeletal health in the form of chronic diseases or fractures.

Based on this measurement, they found that 31% of the total population had functional vitamin K insufficiency, with significantly higher levels among the elderly and subjects with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease.

We may be sub-clinically deficient as early as childhood!

Another study tested vitamin K2 status and supplementation with a group of 110 healthy participants, 42 children and 68 adults. Analyzing 896 blood samples for undercarboxylated VKDPs osteocalcin and MGP, they found that children and adults over the age of 40 show the largest K2 deficiency.

What’s causing this widespread deficiency?

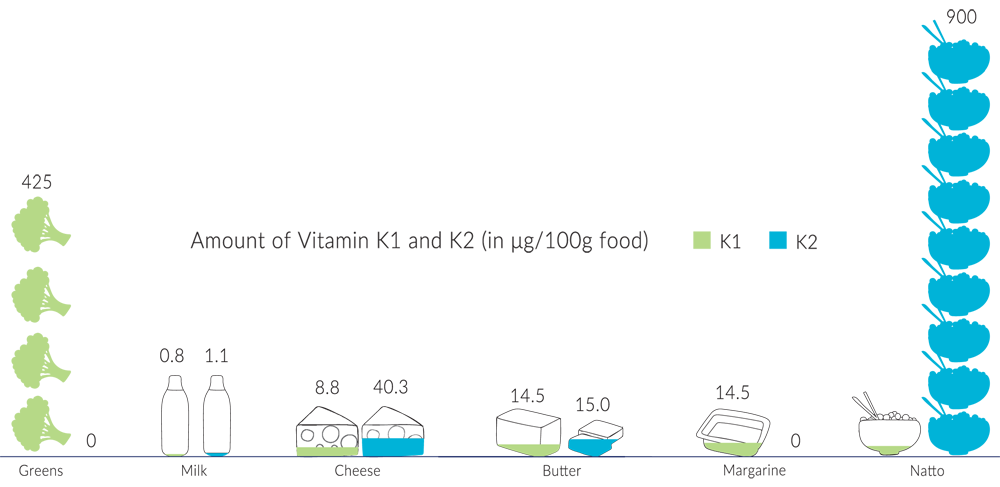

Unlike vitamin K1, which is easily found in green leafy vegetables and plant oils, vitamin K2 is microbial in origin and is much harder to find in our diets.

If you recall the expeditions of Dr. Weston Price, he noted that many pre-industrial societies had traditional foods that were rich in fat-soluble nutrients. Traditional foods like fish eggs, butterfat from grass-fed cows, cured meats, kefir, sauerkraut, organ meats, and aged cheeses. Foods we now understand to be rich in vitamin K2.

Foods that are no longer very common in the modern North American diet.

After all, how often do you tuck into hearty servings of goose liver pâté, brie, gouda or prosciutto – fermented foods that used to be cornerstones of a healthy European diet? It’s easy to forget that our diets have changed tremendously in the past century. And as a result of these changes, we are consuming much less K2 than our grandparents did.

Today’s Japanese palate still features many popular fermented foods, such as pickled vegetables (tsukemono), pickled plums (umeboshi), miso soup and tempeh. However, one dish stands out for being the highest dietary source of vitamin K2 MK-7 in any food: natto.

Today’s Japanese palate still features many popular fermented foods, such as pickled vegetables (tsukemono), pickled plums (umeboshi), miso soup and tempeh. However, one dish stands out for being the highest dietary source of vitamin K2 MK-7 in any food: natto.

Dating back to 1000AD, natto is a traditional breakfast dish made from fermented soybeans. The natto bacteria used in this fermentation process is responsible for producing the high concentrations of K2. 100 grams of traditional natto may contain as much as 950mcg of K2 MK-7! You can obtain all the K2 you need eating 15-20 grams of natto daily.

Unfortunately, natto has a reputation for being an acquired taste and is virtually not eaten regularly outside of Japan. It has a pungent odour, sticky to handle, and can be a little slimy. However, given its K2 content, we recommend you at least give it a try!

A big reason why we don’t eat as many fermented, cured or pickled foods is that we no longer need to cure, ferment or pickle to prevent foods from spoiling.

Modern food preservation methods like refrigeration, canning and pasteurization changed our diets mostly for the better. It increased our access to fresh foods year-round, added a great variety to our diet and reduced food prices.

Unfortunately, as our palates changed to favour the new flavours of refrigerated ingredients, K2 rich traditional food sources from traditional preservation methods like fermentation became less popular.

Traditionally good animal sources of vitamin K2 MK-4, like dark meat, butter and eggs, are depleted of K2 today thanks to industrial farming practices.

Traditionally good animal sources of vitamin K2 MK-4, like dark meat, butter and eggs, are depleted of K2 today thanks to industrial farming practices.

Dairy cattle, hens and other livestock produce K2 by converting the K1 they consume in fresh plant sources and grass. That’s why the best K2 sources of eggs, dairy and meat come from animals that are grass-fed, free-range or pasture raised – free to eat their natural diet.

On factory farms, animals are primarily grain-fed. Without their K1 supply, they do not produce K2 in the quantities we expect.

Another big concern is the impact common medications have on the absorption, metabolism and use of vitamin K in the body. While not all the mechanisms of interference are known, many studies have linked prescription and over-the-counter medications to both lower K1 and K2 status.

Another big concern is the impact common medications have on the absorption, metabolism and use of vitamin K in the body. While not all the mechanisms of interference are known, many studies have linked prescription and over-the-counter medications to both lower K1 and K2 status.

Some drugs inhibit vitamin K by design. Coumarin anticoagulants like warfarin interfere with the body’s ability to recycle vitamin K in order to prevent the activation of VKDP clotting factors. Unfortunately, the indiscriminate interference targets both vitamins K1 and K2, preventing the latter from activating other VKDPs essential to our health.

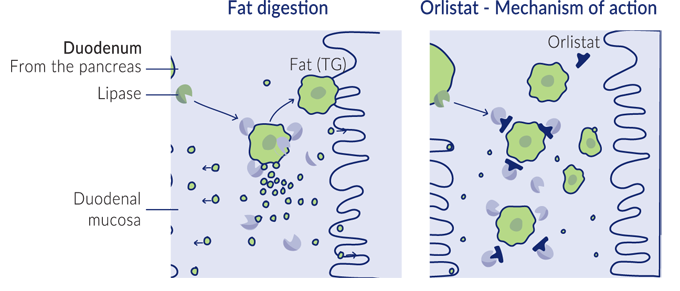

Because K vitamins are fat-soluble, they require fats for absorption and transport through the body. That’s why we absorb less than 20% of K1 from green vegetables (and why adding a good healthy fat like olive oil to your vegetables can help improve that absorption!). Many fat-blocking medications, such as orlistat, interfere with fat absorption and prevent us from absorbing vitamin K in the gut.

Orlistat and other fat blockers work by stopping enzymes in the stomach from breaking down fat particles

It is thought that our gut bacteria are involved in vitamin K absorption. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may interfere with this process.

Ironically, many medications taken for heart disease jeopardize vitamin K2 necessary for good cardiovascular health. These medications typically target cholesterol in the liver. For example, statins block an enzyme in the liver responsible for producing cholesterol. Bile acid sequestrants force the liver to divert more cholesterol to replace lost bile acid.

What does cholesterol have to do with vitamin K2?

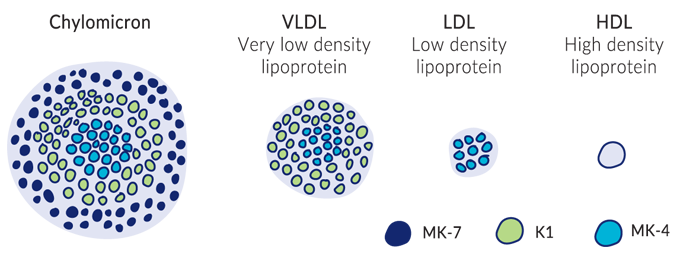

Since vitamin K is fat-soluble, it needs to travel through the aqueous environment of our bloodstream in vessels called lipoproteins. These lipoproteins carry vitamin K to soft tissues and bones all across the body. Lipoproteins are made in the liver using cholesterol.

Not enough cholesterol, results in not enough vitamin K2 movement in the body. The studies back this up, with research suggesting that statin drugs inhibit the formation of vitamin K2.

Given the number of drugs Canadians are taking today, vitamin K2 deficiencies due to medication alone could be widespread. Statistics Canada found that 1 in 10 Canadian adults are taking statins.

Since all K vitamins are fat-soluble, they need fat-friendly lipoproteins to travel through the bloodstream and to different parts of the body

At this point we know what it is, some of the complex roles it plays in the body, and even some of the reasons for why it’s hard to obtain. All well and good. But what you really want to know is whether you’re getting enough vitamin K2.

This is a surprisingly difficult question.

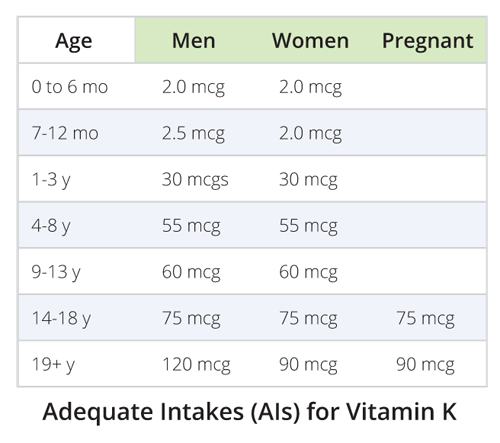

One of the legacies of confusing K2 with K1 is that nutritional authorities still think of vitamin K as one ingredient. When you look up guidelines from agencies like Health Canada, the US Institute of Medicine and the European Food Safety Authority, you will only find official recommendations on vitamin K as a whole, not vitamin K2.

By treating K vitamins as a single nutrient, it’s hard to calculate how much is consumed and absorbed into the body, how much vitamin K is needed in different parts of the body, and how to measure vitamin K status as a whole. With all this confusion, it’s easy to see why these groups struggled to establish recommended dietary allowances (RDA) for vitamin K, only setting adequate intake (AI) levels.

These adequate intakes are still based mostly on our understanding of vitamin K1. A vitamin K deficiency is still clinically characterized only by a bleeding tendency and poor blood coagulation.

RDA is the average daily level of intake that’s sufficient to meet the nutritional requirement for 97-98% of all individuals.

AI is a level assumed to ensure nutritional adequacy, established only when evidence is considered insufficient to set an RDA.

If we look at the current body of vitamin K2 research, we can see that a wide range of doses have been administered.

Some studies have administered pharmacological doses of K2 as high as 45 milligrams of vitamin K2 MK-4 per day. While high dose studies demonstrate the safety of consuming K2 at high doses, they don’t tell us how much we ought to take. They show us safety only, not efficacy.

Other studies have used vitamin K2 MK-7 doses between 90 and 480mcg. Most of the health benefits seem to come from the first 100 micrograms, but higher doses have shown improvements in the form of increased carboxylated VKDPs.

If you’re in great health and taking at least 100mcg of vitamin K2 daily, you probably have nothing to worry about. But if you think there’s room to improve on any of the health categories we discussed earlier, consider a higher intake. Your vitamin K2 status is definitely something worth discussing with your physician or naturopathic doctor.

One of the reasons why it’s so hard to determine a recommended dietary intake for vitamin K2 is that there’s no standard way to test for vitamin K2 status.

One of the reasons why it’s so hard to determine a recommended dietary intake for vitamin K2 is that there’s no standard way to test for vitamin K2 status.

We don’t know enough about how different levels of vitamin K2 in the body interact with each other. What does it mean if we measure vitamin K2 in our blood versus in the liver? Or in tissues versus the bone? Does a low level in one part of the body mean a low level of K2 everywhere else in the body?

And since we do not store vitamin K for long periods in our body, a vitamin K blood test would only measure our recent intake rather than a long-term nutritional status.

Researchers currently assess K2 status in subjects by measuring the carboxylation status of vitamin K-dependent proteins like osteocalcin and MGP. These tests are shown to respond to the supplementation and depletion of vitamin K2 in the body. For example, a high level of undercarboxylated osteocalcin in the bone or undercarboxylated MGP in the blood may indicate inadequate intake of K2 over time.

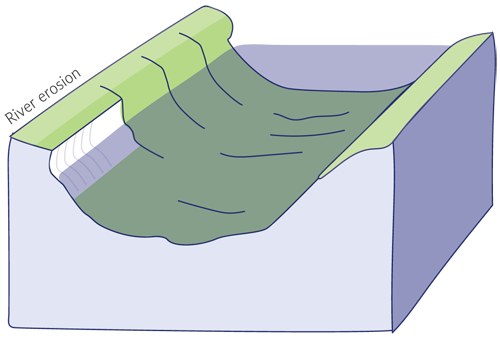

Measuring vitamin K2 status by measuring the carboxylation status of VKDPs is akin to gauging the water flow of a river over time by measuring the erosion of a river bank. A highly eroded river bank may indicate a high volume of water. A high level of carboxylated VKDP may indicate good vitamin K2 status.

The most promising VKDP to measure is matrix Gla protein in the blood. Clotting factors in the liver are acted on by both vitamins K1 and K2. And we don’t know enough about how our bones release undercarboxylated osteocalcin into the blood.

As of this writing, there’s no publicly available tests for measuring undercarboxylated VKDPs. They are only available to researchers right now. But we are optimistic that this kind of testing will be available to you soon.

Doses of vitamin K2 many times higher than typical nutritional intake have been safely administered during large-scale trials. Plus, unlike other fat-soluble vitamins, K vitamins are quickly metabolized, used and expelled – the body does not accumulate large stores of K1 or K2.

Still, it’s important to be careful not to take any supplements at doses higher than what is known to be beneficial. Even if high doses are generally safe, they may have potential side effects that have not yet been studied.

If you are taking prescription medications like anticoagulants, definitely consult your physician or other healthcare practitioner about K2 doses. Blood thinners like warfarin and other 4-hydroxycoumarins work by inhibiting the action of vitamin K. Some studies show that small doses of K2 (up to 50mcg) were able to activate osteocalcin without countering the effects of warfarin.

The best recommendation is to consult with your healthcare practitioner before incorporating vitamin K2 into your daily regimen.

Unlike vitamin K1 deficiency, identified by a bleeding tendency, there is no single sign or symptom that marks a vitamin K2 deficiency. However, certain conditions and risk factors when surveyed together, can provide a clearer picture about your vitamin K2 status.

If you tick off any of the boxes below, you may want to consider increasing your K2 intake.

As vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin, taking a K2 supplement with dietary fat will improve absorption. Try to take K2 with a meal containing healthy fats like olive oil, butter, avocado and coconut oil.

As vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin, taking a K2 supplement with dietary fat will improve absorption. Try to take K2 with a meal containing healthy fats like olive oil, butter, avocado and coconut oil.

You can also try to stack your K2 with other fat soluble vitamins. Emerging research shows the synergistic effects of all four fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K.

In particular, taking vitamin D with K2 ensures the best effect on bone and cardiovascular health. Vitamin D assists with absorbing calcium from the intestinal tract. Without pairing it with K2 to activate matrix Gla protein, this additionally absorbed calcium may accumulate in soft tissue and arteries.

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. It is mandatory to procure user consent prior to running these cookies on your website.

Analytics cookies help us understand how our visitors interact with the website. It helps us understand the number of visitors, where the visitors are coming from, and the pages they navigate. The cookies collect this data and are reported anonymously.

These cookies collect information about how visitors use a website, for instance, which pages visitors go to most often, and if they get error messages from web pages. These cookies don’t collect information that identifies a visitor.

The “Other” category cookies help us provide our visitors proper functionality of the website such as online quizzes or embedded videos.

Advertisement cookies help us provide our visitors with relevant ads and marketing campaigns.

Learn about how vitamin K2 works, why it’s important, and how it can help you.